You are here

Mrs. Ruth K. Roberts: In Memory

Pilling, Arnold R. / Mrs. Ruth K. Roberts: In Memory. Del Norte County Historical Society Bulletin. January 15, 1979, pp.3-5

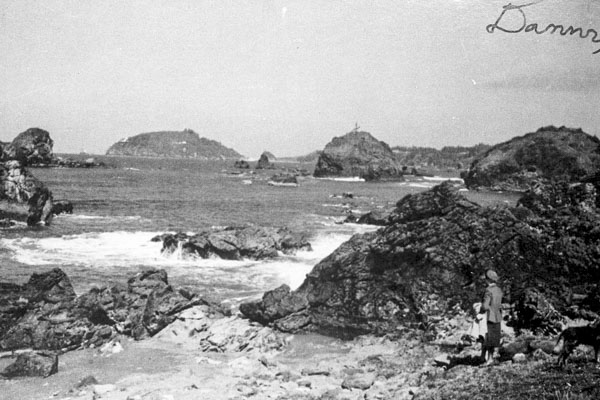

In the fall of 1967, I took a one-term sabbatical leave from Wayne State University to collect what I could of Yurok trouble-cases in order to understand how the legal patterns of this hunting and gathering group had changed from their pre-European Contact form to the present day. In my attempt to find the community where Yurok law could best be studied, my family and I stopped at Crescent City, north of the traditional Yurok territory by about ten miles, but long a center of urbanized Yurok.

The kind hostess of our motel by the second day informed us that I should talk to Mrs. Roberts, as she knew about local Indians.

That first conversation with Mrs. Roberts was awesome. I left feeling as though I had gone for a shower and found myself beneath Niagara Falls. Her command of Yurok and their trouble-cases spanned in detail the era from 1915 through 1933, when she had spent the late spring through fall of each year at the mouth of the Klamath River, where her husband was chief bookkeeper for a major commercial salmon cannery. She knew less well the era from 1933 to 1955; for in those years she had not lived on the Klamath River among the Yurok, but she had opened her Piedmont home to them and, thereby, kept in touch with her Indian friends. Since 1955, she had lived as resident curator of each of the three museums maintained in Crescent City by the Del Norte County Historical Society, as well as having supervised the reconstruction of its fourth installation, the restored Yurok family house at Requa, at the mouth of the Klamath.

Reflecting back now on September and October afternoons in 1967, when we talked, Mrs. Roberts and I, at the main Del Norte County Historical Museum, I realize that her body must have been wearing out. Her balance was no longer steady, and her vision was limited. But the spirit, the drive, the desire to help her fellow man, especially her Indian friends, were still so strong that to a new acquaintance she conveyed the impression that the little problems of aging were but the commonplace sort of challenge that were easily met and always passed over - no more than the irritations of the moment.

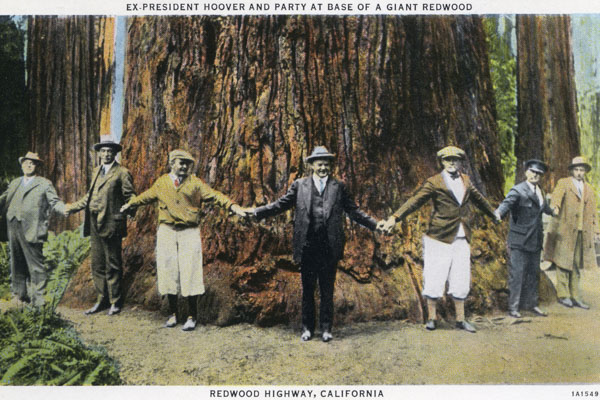

When I could convince her to rest herself, to stop even momentarily from working on displays, on the cataloguing of the ever-increasing collection of specimens which rarely lay as long as a week without being totally processed, she sat on the polished oak bench, which was like a great church pew, to the left of the entrance of the museum. It was her Museum - not that she ever referred to it as "hers" - that old County Hall of Records and Jail. She had cajoled and pleaded with officials to turn it over to the Historical Society when it became otherwise unwanted surplus. Here in the Indian Room she met the tourist who paused momentarily to look more deeply at Crescent city, than at the beautiful coastline and the towering redwoods nearby. Here, too, she told the tale of the Del Norte County history to nearly every class of school children in the county. Her talk to each class started the same:

The first White Man to enter Del Norte county was Jedediah Smith...But long before Smith came, the Indians owned this country....

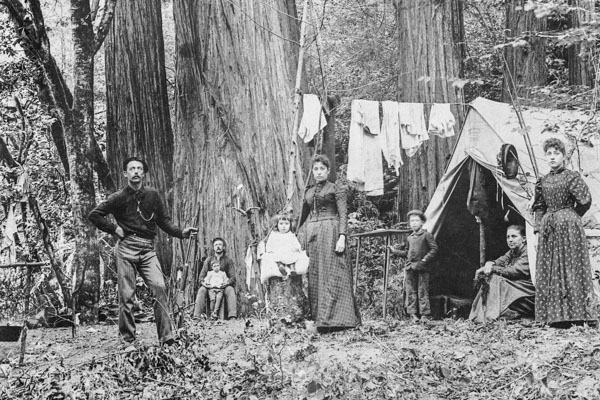

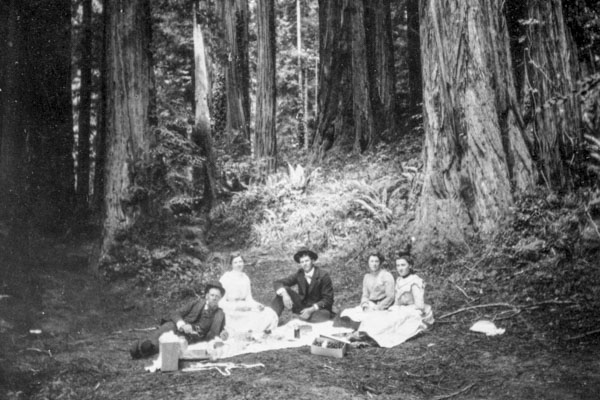

For in some fashion, the real way, the true way of life in Del Norte County was the old Yurok and Tolowa way: of salmon roasting on sticks on the beach; of poling up "The River" (the Klamath River) in the old smooth-bottomed, flat ended Yurok dugouts; of the walks over the gravel bars on The River to lighten the load when the boat had to be towed upriver through the riffles; of the great old First Salmon Rite at Requa.

Long before I met Mrs. Roberts, nearly twenty years [ago], I knew her, not her name. I had even referred to her in lectures on cultural change. Those who were familiar with the details of Yurok culture history in the first half of the 20th century knew that there had been a society lady from Piedmont, who had for years arranged for young Yurok women to work in Piedmont homes. There, these "girls" could learn of the world outside, beyond the land of lumbering and salmon-fishing, which since the 1860's had been the life of Humboldt and Del Norte Counties, the homeland of the Yurok. That legend was Mrs. Roberts. Shortly after 1915, she began her one-woman battle for California Indian rights, using as one her approaches this exposure of Yurok young ladies to the wealthy homes of the East Bay of the San Francisco area. In 1927, she also worked for the law to guarantee California Indians the right to vote.

When Mrs. Roberts and I talked, a [flood of] familiar names from the past came forth, names that had first made the Department of Anthropology at Berkeley famous. She seemed to have known nearly everyone associated with anthropology at Berkeley in the early era; she referred to "Dr. Kroeber, Mr. Gifford, Dr. Barrett, and (T.T.) Waterman." She spoke with reverence of Robert Spott, Kroeber's chief informant. She talked of Alice Spott - Robert's sister and Mrs. Roberts' closest friend, and of George Flounder - the last medicine man of the Capel fish rite. By 1967, they were all gone. Yet they were not. For me, entering Yurok field work during the fall of 1967, they still lived - in stories, in photography. The culture they had known among the Yurok was still vivid in Mrs. Roberts' memory; her snapshots from the late teens and early 1920s showed a way-of-life which has now disappeared.

Mrs. Roberts made it obvious. It was essential that my wife and I had to go to Hoopa to see the white Deerskin Dance. We went twice. A few weeks later, Mrs. Roberts intimated we had to see the Jump Dance; we must not miss that. We knew that the Yurok did not perform it any more on the Klamath, but some Yurok participated at Hoopa. We went one week-end and saw it.

Then I sensed some way, Mrs. Roberts would like to see the Jump Dance; there was only one last week end - the finale of the 1967 ceremonial season. I called Mrs. Roberts: "Would you and Teresa (her housekeeper, one of the Indian "girls" of years ago in Piedmont) come up to Hoopa with us?"

The answer was rapid. "Nothing could mean more. Of course. I have gone up the river when I was so sick, I was sure I would die. But I wouldn't miss it - no matter what!"

I think we both knew it was her last Jump Dance. I might add it was probably her first in over forty years since a Yurok one about 1927 which she had attended with Alice Spott. One of the greatest dancers danced. His heart was bad; he was never supposed to dance again. She had not seen him dance since he was about 25, when Mrs. Roberts and her husband were very close to him. He danced and it was a great dance, the last dance, when the old Hupa and Yurok cry in memory of all the great dancers and singers who are now dead, but once performed so magnificently.

There were only a few days left after we returned from the Jump Dance. I did not feel this, but Mrs. Roberts must have known. There was a rush about the way she felt she should be showing me the many things which she had not previously. She artfully arranged her time so she could introduce us to the best surviving Yurok informants, to show us each of the old village sites.

She was too weak to go to the Tolowa Indian Cultural Society meeting jointly with the Smith River Women's Club. The next day she was hospitalized. Indian friends came in streams, the Tolowa from Smith River; the Yurok from Crescent city, from Starwen, from Elk Valley, and from Martin's Ferry; even a Chetco friend. Mrs. Roberts was the gracious hostess; she would not be critically ill.

Mrs. Roberts will be sorely missed in Del Norte County. The Historical Museum cannot readily find her replacement. Her genteel, but persuasive, approach is no more easily duplicated than her broad command of local history, both European and Indian. A memorial fund has been established in the Historical Society, to be used for the purchase of rare Indian heirlooms. The Indian Room is now the Ruth K. Roberts Indian Room.

To her Indian friends, there can, of course, be no equal. Each elderly Yurok seemed, most personally, to speak of her in the same way: "She was my friend." One lady said of a project which Mrs. Roberts did not finish, the only one of her attempts at the preservation of Indian history which she left incomplete: "But who will do it now?"

Like the great departed singers and dancers of the Yurok and Hupa ceremonies, each was unique. Each had his own style. The old Yurok cry in memory of a great performer.

Written:

By A.R. Pilling

Detroit, Michigan

January 1968