You are here

The Roberts Collection of California Indian Photographs: A Brief Review

Palmquist, Peter E. / The Roberts Collection of California Indian Photographs: A Brief Review. Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology. Vol. 5, Nos. 1 and 2, pp. 3-32 (1983)

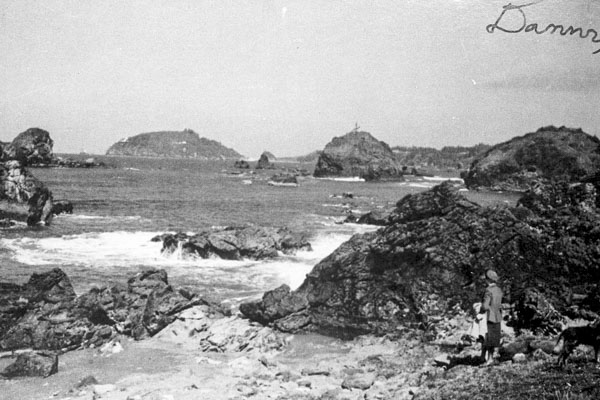

Some of our most interesting collections of native American photographs are virtually unknown outside the region of their origin. The collection of photographs taken by Mrs. Ruth K. Roberts and now in the Humboldt Room, Library, Cal Poly Humboldt, Arcata, California, is an example. The collection consists of 536 images and contains a large number of original negatives of the northern California coast from Crescent City southward to the mouth of the Klamath River. These, together with copy negatives of original photographs collected by Mrs. Roberts, form a remarkable document of Indian life in the region from about World War I into the 1950s.

Twenty-nine photographs from the collection are shown here. The captions are based on notes originally written by Mrs. Roberts, many of which were made at the close of her life when she suffered greatly from failing eyesight, and include additions by her son, Harry, "whose memory of events some fifty years before was not necessarily very good." Dr. Pilling has continued to investigate the accuracy of these notes and has clarified some (Arnold Pilling, personal communication 1983). All captions are quoted from Pilling (1969).

The unifying trait which separates this collection from similar ones rests with Mrs. Roberts herself; she photographed her special friends, an extended family of northcoast Indians. The images are personal and, for the most part, wonderfully natural. They avoid the stilted and graceless artificiality so often observed in native American photographs made by photographers less intimately involved with their subjects.

Mrs. Roberts was an amateur photographer. She used simple roll-film cameras in at least four different formats over the years that she visited the region. Many of her photographs are out-of-focus or poorly exposed. Yet, despite her lack of camera expertise, she also made images of lasting beauty. Mostly they are remarkable documents of people, places, and events which meant so much to her. Her images of the lower Klamath River are particularly important records of the veritable twilight of traditional native life. Her photographs include individuals and families who were primarily of Yurok ancestry.

Dr. Arnold Pilling, Department of Anthropology, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan, deserves all credit for recognizing the unique nature of Mrs. Roberts' photographs. In the fall of 1967, he took a short sabbatical leave and traveled to Crescent City where he met Mrs. Roberts. Together, they visited Hoopa to observe the Jump Dance which was the finale of the 1967 ceremonial season, and to see Dewey George, one of the great Yurok dancers. When they returned, Mrs. Roberts became critically ill; it was her final season among the people she had come to love and cherish.

The Roberts collection was given to Dr. Pilling by Harry Roberts, the only heir and child of Ruth Roberts. This transfer was in recognition of Dr. Pilling's special interest in the material, and there were no stipulations connected with the gift. It was Dr. Pilling's decision to give the Roberts photograph collection to Cal Poly Humboldt, although he still retains the original copies of manuscript material and some original photographs from negatives for which only copy negatives are known.

Struggling to preserve Mrs. Roberts' special knowledge, Dr. Pilling immediately worked to assemble her notes and photographs into the collection now known as the "Roberts" collection. He also eulogized her in an article in the Del Norte County Historical Society Bulletin. Mrs. Roberts was past president of the historical society and past curator of both the McNulty Pioneer Home and the society's museum. Dr. Pilling's article clearly reveals his great respect for her:

Long before I met Mrs. Roberts, nearly twenty years [ago], I knew her, not her name. I had even referred to her in lectures on cultural change. Those who were familiar with the details of Yurok culture history in the first half of the 20th century knew that there had been a society lady from Piedmont [California], who had for years arranged for young Yurok women to work in Piedmont homes. There, these "girls" could learn of the world outside, beyond the land of lumbering and salmon-fishing, which since the 1860's had been the life of Humboldt and Del Norte Counties, the homeland of the Yurok. That legend was Mrs. Roberts. Shortly after 1915, she began her one-woman battle for California Indians' rights, using as one her approaches this exposure of Yurok young ladies to the wealthy homes of the East Bay of the San Francisco area. In 1927, she also worked for the law to guarantee California Indians the right to vote [Pilling 1979:4].

That first conversation with Mrs. Roberts was awesome. I left feeling as though I had gone for a shower and found myself beneath Niagara Falls. Her command of Yurok and their trouble-cases spanned in detail the era from 1915 through 1933, when she had spent the late spring through fall of each year at the mouth of the Klamath River, where her husband was chief bookkeeper for a major commercial salmon cannery. She knew less well the era from 1933 to 1955; for in those years she had not lived on the Klamath River among the Yurok, but she had opened her Piedmont home to them, [and] thereby, kept in touch with her Indian friends. Since 1955, she had lived as resident curator of each of the three museums maintained in Crescent City by the Del Norte County Historical Society, as well as having supervised the reconstruction of its fourth installation, the restored Yurok family house at Requa, at the mouth of the Klamath [Pilling 1979:3].

When Mrs. Roberts and I talked, [the] familiar names from the past came forth, names that had first made the Department of Anthropology at Berkeley famous. She seemed to have known nearly everyone associated with anthropology at Berkeley in the early era; she referred to 'Dr. Kroeber, Mr. Gifford, Dr. Barrett, and T.T. Waterman.' She spoke with reverence of Robert Spott, Kroeber's chief informant. She talked of Alice Spott--Robert's sister and Mrs. Roberts' closest friend, and of George Flounder--the last medicine man of the Capel fish rite. By 1967, they were all gone. Yet they were not. For me, entering Yurok field work during the fall of 1967, they still lived--in stories, in photography. The culture they had known among the Yurok was still vivid in Mrs. Roberts' memory; her snapshots from the late teens and early 1920s showed a way-of-life which has now disappeared [Pilling 1979:4].

During the assembly of the Roberts collection, Dr. Pilling made a careful and thorough assessment of any, and all, notes associated with the material. Dr. Pilling has long been a champion of photographs as documents and his interest dates from about 1935 when he began collecting photographic postcards. (Pilling 1974). His avid interest in collecting Indian photos began in 1949. A xerox copy of his notes, together with additional supportive materials, is available with the Roberts collection at Cal Poly Humboldt (Dr. Arnold R. Pilling, compiler, Pilling Catalogue and Miscellaneous Materials Relating to the Roberts Collection).

References:

"Requa: Indian Woman Paddling a 'Double-ender'" (RS-28). The image is of Alice Spott (Taylor) paddling a pre-World War I ocean-going canoe. Such a canoe was also used for travelling on the Klamath River. The paddle which Alice is using is a "wide paddle," which was used to paddle, rather than pole, a canoe on the river.

"Wilson Creek Beach: A Partly Worked Canoe, Drifted in as a Log" (RB-6).

"Requa: Yurok Indian Woman" (RM-33).

"Pecwan: Jump Dance Leader" (RB-10). The man pictured is Waukel Harry. He is holding "white eagle" feathers, actually the feathers of the Gyr Falcon, from the Arctic.

"Pecwan: Dance Outside the Dance House" (RB-25). This is the first part of the Jump Dance; this dancing is not for the public, but a sort of prayer dance before the dancers dance in the pit, in public. Yurok and Hupa women do not look at this part of the dance. The Roberts photos are the only known [photographs] of this most sacred part of the Jump Dance.

Dancers entering, single file, the dance pit at the 1926 Pecwan Jump Dance. Note one of the "dance masters," i.e., regalia custodians, adjusting the feathers of a dancer before the dancer enters the pit (RL-41).

"Pecwan: Jump Dance, Probably in 1926. Dancing in Pit" (RB-40).

"Johnsons: A Street Scene" (RM-17). This is the view, about 1926 of the main corner in Johnsons, the road descending towards the right goes down onto the river bar. Note the clothes hanging from a grave in the right center of the image.

"Johnsons: A Street Scene" (RM-16). [Pilling notes that this label is incorrect]. The old trail in the foreground is that between Oregos, or Tucker's Rock, and Rekwoi. The buildings are, from left to right: the Spott House; behind the bushes and barely visible, the Spott family house; the Spott wagon house; the Brook's house, the "Great House" of Rekwoi, which still survived, now much modified; behind the Brook's House is the old Spott cemetery; and the Brook's old barn.

"Johnsons: One of the Sweathouses" (RB-46)

"Johnsons: The Yurok Cemetery with 'White Man' Dwelling at Rear" (RL-71). Note clothes hanging from a rod over one of the graves.

"Requa(?): Harry Roberts and Indian Woman Holding a Good Fish Catch" (RS-53). Photograph of Alice Spott (Taylor) and young Harry Roberts about 1917. Note that Alice Spott, who had made "medicine for the strong" has her hair done in the top knot of a warrior, as is appropriate for a woman who was a fisherman, only "medicine trained" female being able to fish. The notch at the left of the image is that marking the canyon of Blue Creek; the bluffs are to the left. The foreground is the "lower Knapp Place" on the Klamath River bar. The Spott family had fishing rights from the rocks at the river bank on the opposite shore. Alice Spott brought her fishing net with her when she travelled. When this photograph was taken about 1917, the "old law" was still in effect and she would not use another's fishing spot.

"Requa: Yurok Grandmother in 'Double-ender' Canoe" (RB-59). Susie Crutchfield, probably with her son, the late Ed Crutchfield, at the stern. "Howinquit: Surf Fish Drying, in Smith River Pattern" (RS-59). Tolowa territory.

"Klamath River: Double-ender, Loaded, on River" (RS-31). [Pilling notes caption incorrect.] The canoe is an "old-fashioned" one. Note baby basket on woman's back, also the "fancy" basketry cap being worn.

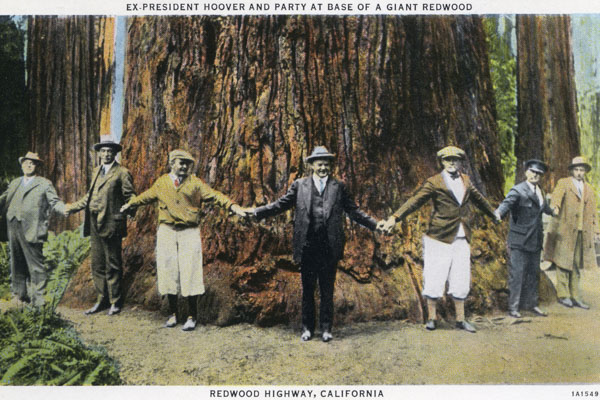

"Requa: Ter' -per Rock on the North Shore of Klamath River" (RL-64). "In the Redwoods, the 'Redwood Highway'" (RL-62).

"Johnsons: Nora John, Sister of Lucy Thompson" (RM-76). Nora John is the biological mother of Bertha and Allen Thompson; Lucy Thompson was their step-mother, as well as their mother's sister. James Thompson first was married to Nora, and was then abandoned by her when she married a full-blooded male. Jim kept the children and next wed Nora's childless sister.

"Indian Woman and Tame Deer" (RL-15). The image is of Alice Spott (Taylor) and her pet deer.

"Johnsons: The Stone-ended Sweathouse with Puppy on It" (RS-74). "Wilson's Creek: The Site of Omen from Southwest Looking Across 'Plywood Mill Creek'" (RB-56).

"Klamath River: Mrs. Ruth Roberts by Main Entrance to Sweathouse" (RS-50). Photograph taken in the early 1920s. Note the elkhorn wedge marks on the board above the entrance.

"Pecwan: Group of Indian Children at Jump Dance; or, Requa: Group of Indian Children, Probably at Safford Island Indian Day" (RL-12).

"Requa: Group of Children in Front of Brook's House" (RL-51). The baskets are, left to right, acorn holding basket, hopper mortar basket, acorn flour sifter.

"Johnsons: Stick Game in 1926" (RB-44).

"Requa: Brush Dance" (RM-35).

"Requa: Mary Ann Frank, Standing Before Brook's House" (RL-54).

"Requa: Captain Jack Beating a Gambling Drum" (RL-13). Taken adjacent to a building owned by the Gensaws, at Requa.

(RL-48) [ See caption for RL-13; reproduced in Wallace (1978: Fig.8)].